A disclaimer

The purpose of the following is to add structure to certain ideas I've been thinking about. This is a tool to clarify my thoughts and so any reader should be skeptical of any assertions I make. I'm not an expert in any of these fields, but will attach resources to those who are. Beyond this aim, my hope is that the following may allow readers to share in the excitement and enjoyment of learning as I very much have and continue to do.

The question of logic, its value and use may either appear trivial or unimportant. Those who program or design systems will undoubtedly know of its use, but may have not spent much time on determining its value. Conditional statements (e.g. if-then clauses) are used to control steps of computation. They allow different actions to be taken for different inputs. Logical operators ( e.g. AND, OR, NOT) are filters to validate and select upon different inputs. They allow one input to be differentiated from another. The combination of these two classes, allows a path of computation to be constructed. Assume one only has these two methods available to them, can anything of interest be created, and if so, then why?

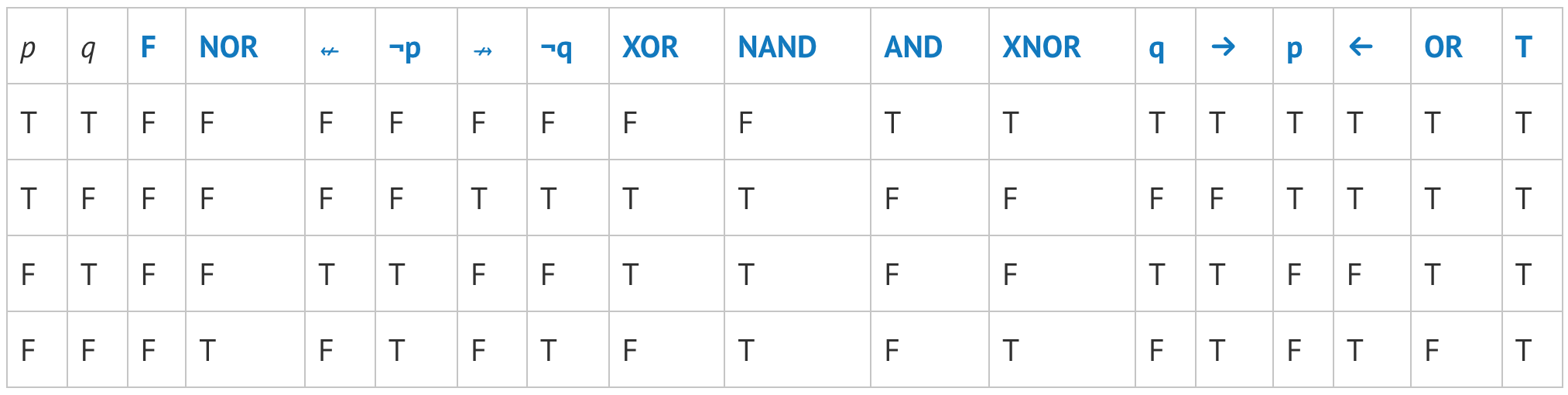

In the second class, which will be the focus in this post, logical operators have to operate on something. In classical logic, this would consist of propositions. The law of the excluded middle requires each proposition to either be true, or the negation of the proposition to be true. A statement can’t be TRUE and FALSE at the same time. The operators we are interested in are binary operators, meaning, we take two propositions and return a TRUE or FALSE designation. We can think of propositions as the variables p and q, each of which will have a T or F designation. We can now construct all possible arrangements. We know there will be 16 in total because we have two propositions, each with two designations. 2 * 2 gives us four arrangements. Therefore, each binary operator will have 4 results. We take 2 * 2 * 2 * 2, or 2 4 which equals 16. All of these operators have been studied and are listed below.

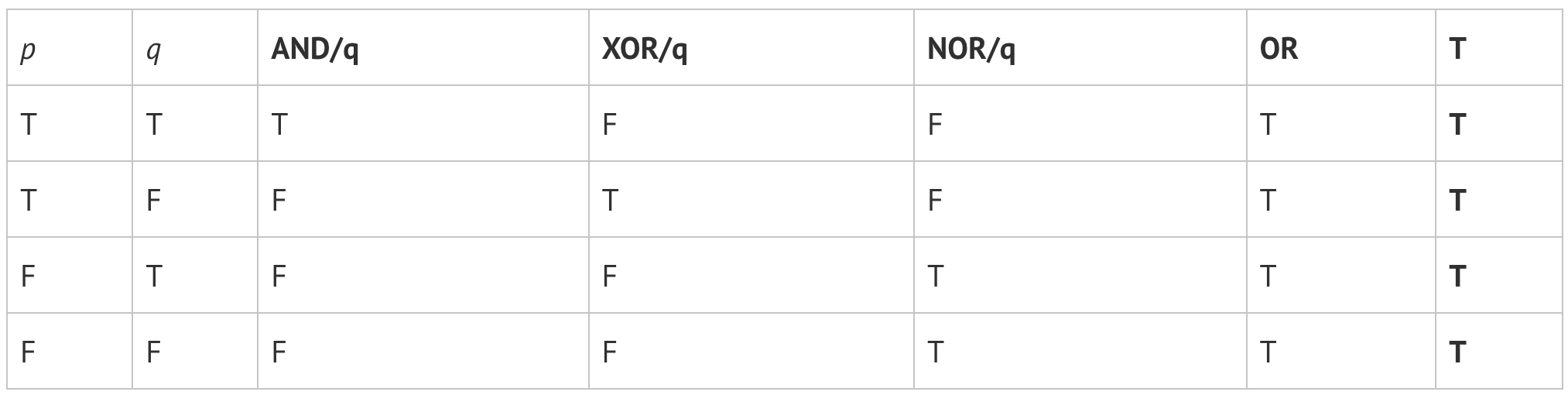

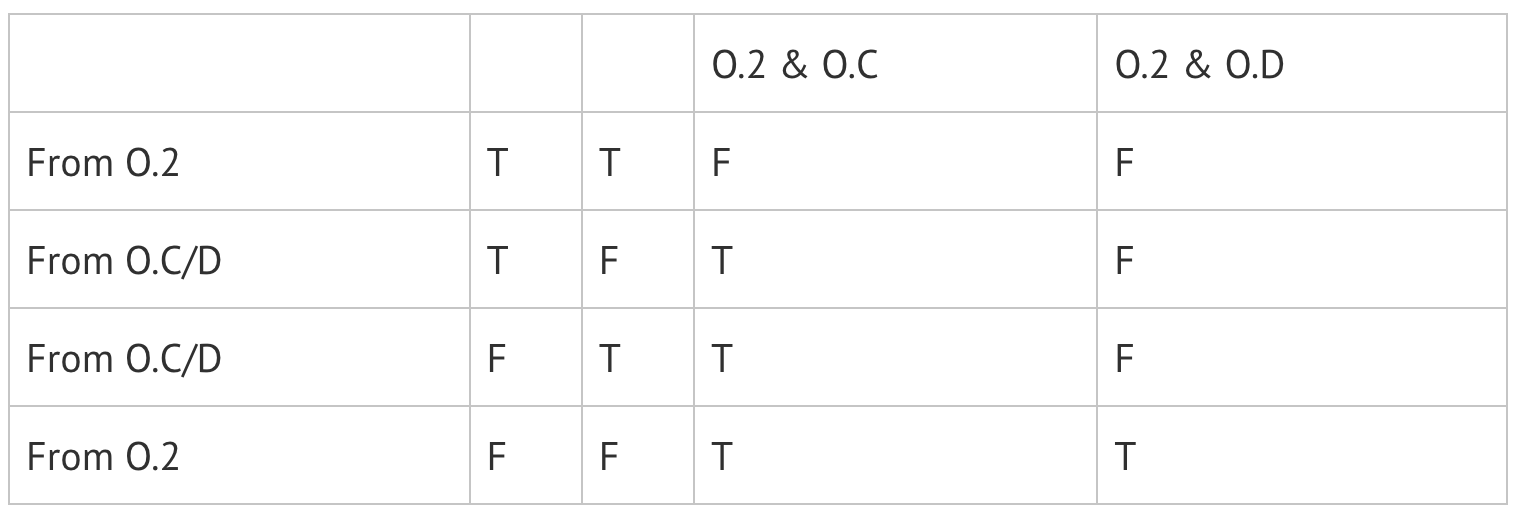

First, we should note that we can’t escape these binary operators. No matter how many of these operators you chain together and apply, you will always end up with just one of them. For example, let’s say I have p, q and apply the following operators in order by taking the result and substituting it in for q.

Above, we can see the chain of AND -> XOR -> NOR -> OR produces all TRUE values. This is the same if we applied the T operator to p and q to begin with. A natural question is if there is any one binary operator that can generate all of the others. There happens to be two, and this property is called functionally complete. The follow up question has to do with why only these two work.

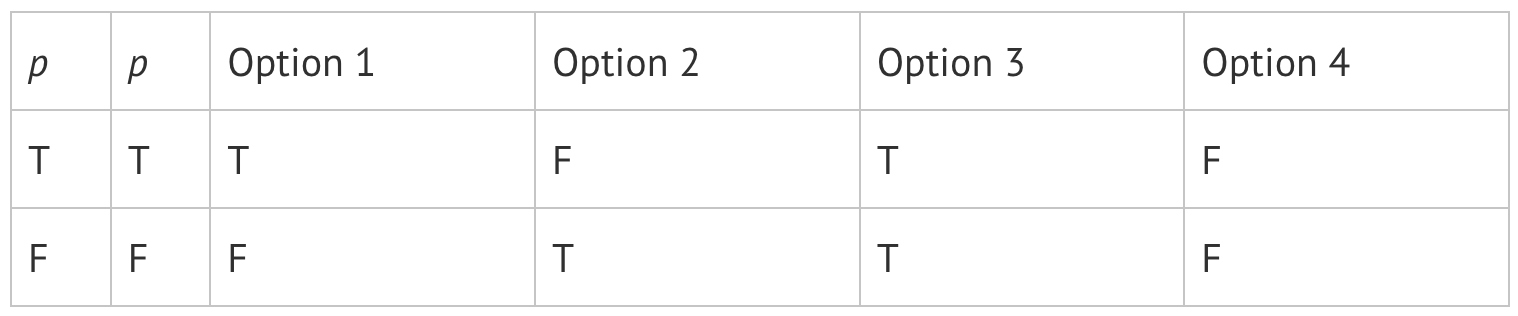

My explanation revolves around information loss. I will clarify after the following presentation. Let’s say I have p and p. Then there is some operator that will return p back, the negation of p, which we will represent as ¬p, or something different labeled k. If I apply the operator again with the result, either I get p back again, the negation of (¬p), represented as ¬¬p, which becomes p, or k. How am I certain we get back k instead of some other value say p or even j? We can, of course, look at some more tables. We’ve simplified p because it’s just with itself, if you were wondering why it doesn’t look like the table above.

O.1: we get back p.

O.2: we get back ¬p.

O.3: we get back k.

O.4: we get back k’.

We can analyze the rules that created k. If we have both T or F, we get F. It basically kills our input and flatlines it. To show this, we can set the result of each case to p and run the cases again.

O.1 will still return the original p.

O.2 will now return ¬¬p, which becomes p.

O.3 will return k.

O.4 will return k’.

Please check this, if you are so inclined.

The corresponding chains are

O.1 => p -> p -> p -> p …

O.2 => p -> ¬p -> p -> ¬p …

O.3 => p -> k -> k -> k…

O.4 => p -> k’ -> k’ -> k’…

Now if our goal is reach p, ¬p, k and k’ with one operator. (Remember each option can also be thought of as an operator. We take two inputs and operate on it.) We have to think about which option we are going to want to take. If we take O.1, we are left in an endless loop of repeating the input. This doesn’t help us.

Now O.3 and O.4, even though we get p and k or p and k’ we enter into a loop of repeating k or k’. This will flatline us and we lose the ability to regain p. We lose the information of p. This leaves us with exploring O.2. Even though we only get p and ¬p, we can now use this to create 4 more operators. With O.2, we gain a state while not losing our original state. No information loss!

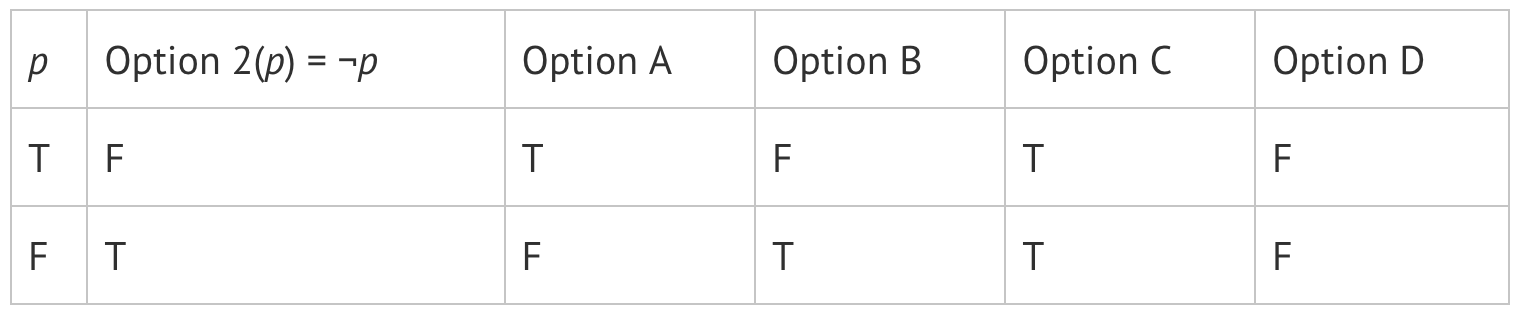

So instead of running p with itself, we run p with O.2(p). These operators are different because they will end up take a T and a F as input or vice versa. The O.1..4 operators took two Ts or two Fs. These new cases follow:

O.A will return p.

O.B will return ¬p.

O.C will return k.

O.D will return k’.

Now these two return the same output as our O1..4 after one iteration. This is because we constructed the output in a certain order. Remember that this is exhaustive and because of this we are allowed to label them anyway we like, as long as we cover all cases. O.1 isn’t the same as O.A. They output the same, but arrive there differently. O.1 must take two Ts to make a T, while O.A must take a T and a F in that order.

Now we can run this again, by taking the output as our new p and then running O.2(p) to get the negation.

Option A will return p. Chain: p -> p -> p -> p …

Option B will return p. Chain: p -> ¬p -> p -> ¬p …

Option C will return k. Chain: p -> k -> k -> k…

Option D will return k’. Chain: p -> k’ -> k’ -> k’…

Exactly the same chains! We’ve forced the output to be the same, but the underlying operation is different.

So we have these new chains. Our goal is still to get p, ¬p, k and k’ and we have p and ¬p from O.2. Problem is, it looks like we can only get k or k’. Dang! We must now examine k and k’. They are clearly negations of each other. Now if we use O.2 to negate k or k’ then we should be in business. So let’s say we chose O.C. We now have the ability to get p, ¬p, and k.

Now if we want to return k’, we can chain our operators together. We take O.C(p) => k, then immediately apply O.2(k) => k’. Give this a try. This is very cool. It means we hit every possible outcome that we are interested in. To note, we don’t necessarily need to take O.C, we can take O.D. So with all this information, we can construct our two tables fully, by combining Option 2 and Option C into one operator.

If we look back to our table of 16 we will find that both operators are NAND and NOR and these are the two operators that are functional complete!

Before moving on, one may be tempted to say, “hey, why can’t I use Option B and then Option 3 or 4?” I’ll leave it up to you to show how this doesn’t work. Also we can use any option for O1..4 and then pick any option from OA..D to construct more operators. We will eventually run out after we’ve found 16 though.

Observations

From this analysis, we’ve shown that it is essential to have our negating option and one that results in k or k’. Our negating operator adds the ability to access a new state and we use that new state, ¬p, to construct the ability to access a new set of operators. Through this new set of operators we can select k or k’. In a sense we gain the ability to arrive at new information, ¬p.

What is also very cool is the fact that p could even be just our operator, NAND or NOR, meaning we don’t even have to be supplied with p to begin with. We can just take NAND as our p and start cranking away at making all the other operators. The hardware in computers does this. Play this game nandgame.com to explore this idea much more!

There’s a few more open questions, that we may touch on next time.

- Is any information gained when we chain a bunch of operators against each other if they are bound to result in just one of the 16 variants?

- Computers operate using these operators as models, so clearly there must be “information gain”, but it might not be so clear how or why that’s the case.

- Does this trend extend for ternary operators, taking 3 arguments? Does this trend extend into worlds where we have more that T, F?

- These are all questions math can tackle. Group theory comes to mind.

- Have we done anything of value?

- T and F don’t have any real meaning from what we’ve done. We all know what TRUE or FALSE means but that is something we add on to the symbol T and F. We could have used any two symbols and everything still holds.

One final observation, that is crucial to making this whole thing work is our ability to freely generate copies of our input. If we can’t do that, then we get stuck. I’m not sure we can do much of anything. We’ll talk about the implications next time and move from classical logic to linear logic.

Resources

Two Puzzles about Computation by Samson Abramsky

The Nature of Computation by Moore and Mertens

This page is a post.